Euro-Americans were more interested in settled agriculture in the Old Northwest than they were in sustaining the fur trade that had characterized the region for more than a century. Americans aggressively pushed Indians to become virtually indistinguishable from themselves, or failing that, to relocate them from areas of American settlement altogether, a political development that came to characterize US relations in the 1800s with Indian nations westward all the way to the Pacific.

The haunting stories of the forced removal of tens of thousands of Indians from their homelands—such as the Cherokee Trail of Tears—were in many ways a direct result of the War of 1812’s outcome and the power shifts in North America.

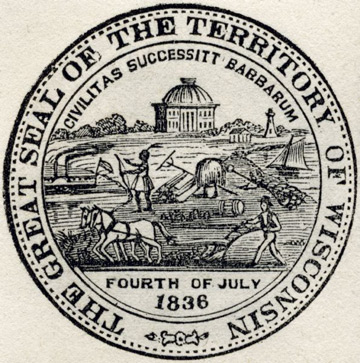

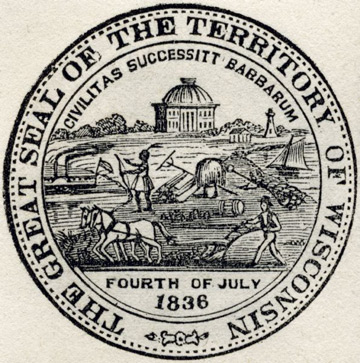

Removal was sometimes presented as a benevolent process. Lewis Cass, for example, the governor of the Michigan Territory from 1813 to 1831, believed that removing Indians to territories west of the Mississippi River would be the only means of ensuring Native American survival during a time of encroaching American settlement. Regardless of Cass’s rationale, his role in negotiating the Treaty of Fort Meigs (1817) signaled the formal cession of all Indian territory in the Ohio Valley. In 1836, then US Secretary of War, Cass wrote: “the Indians now holding lands in the vicinity of Green Bay can only be considered as temporary residents there.” From the perspective of individuals like Cass, the Mississippi River would become the new dividing line between Native and US settlement. Less than a century earlier, at the conclusion of the French and Indian War, the British had similarly proposed a dividing line that was as far east as the Appalachian Mountains. The Americans were focused on territorial expansion.

With the election of President Andrew Jackson in 1828, the adoption of Indian westward removal as official federal policy became an inevitability. Implementing the Indian Removal Act (1830) became one of the highest priorities of Jackson, a frontiersman from Tennessee and a famed Indian fighter who was interested in developing the region west of the Appalachians. Some tribal communities sought to avoid removal and maintain their territorial integrity by patterning their lives after Americans to demonstrate their ability to peacefully coexist and successfully adopt the “civilized” and Christian ways of their white neighbors. Jackson, however, was skeptical of Indian incorporation into American society and ultimately believed that Native people forestalled the development of the trans-Appalachian region and still posed a threat as potential allies to the British.

The Indian Removal Act authorized the negotiation of treaties that would exchange Indian lands in the east for land in the unorganized territories of the trans-Mississippi West. The prospect of removal sharply divided many Native communities, with some tribal members completely opposing removal and others hoping to actively negotiate for the most favorable terms possible in light of what they believed to be an inevitable process of forced relocation. Under significant external pressure, some groups did voluntarily move west; such stories complicate the dominant historical narrative, which maintains that the United States simply swept away the vestiges of Indian communities in the east. Nonetheless, the US military and volunteer militiamen forcibly uprooted many communities that did not willingly move westward across the Mississippi River.

Within three decades of the war of 1812, the policy of Indian removal had dramatically transformed the map of Native America and traumatized entire indigenous communities. The haunting stories of the forced removal of tens of thousands of Indians from their homelands—such as the Cherokee Trail of Tears—were in many ways a direct result of the War of 1812’s outcome and the power shifts in North America. The removal policy contributed to the wide dispersal of tribal communities beyond their original homelands. For instance, forced migration partly explains why there are currently Potawatomi communities in four states: Kansas, Oklahoma, Wisconsin, and Michigan. However, Indian removal in the Great Lakes region was neither total nor inevitable. Indeed, many Native people resisted removal after the Americans gained control of the region. Many Ho-Chunks, for example, returned east to Wisconsin even after their forced relocation to Nebraska.

The era of removal was also a period of Indian land cessions. Faced with the possibility of military force, many tribes throughout the Great Lakes region agreed to massive reductions of their land base. Instead of being forced westward, many Native people were banished to isolated reservations that were generally undesirable for white agricultural purposes. Native communities were often sharply divided when faced with such removal and land cession pressures. In Michigan, Wisconsin, and Minnesota, nearly the entire Ojibwe homeland—except for a handful of small reservations—had been taken through a series of treaties by 1867.