By Ann D. Gordon

The year 2020 marks a significant centennial: ratification of a federal constitutional amendment that barred states from excluding women from the electorate solely on the basis of their sex. We pay tribute to the tens of thousands of women who envisaged a government in which men and women had equal voice and who, through agitation and persistent mobilization of citizens, brought about that change. This was a long fight. Historians point to different moments of origin, but their choices fall into the 1830s and 1840s. If dated from the women’s rights convention at Seneca Falls , New York, in 1848, seventy-two years passed before ratification of the federal amendment—and that’s the short version.

As we celebrate, it matters that we not overstate the changes wrought by the Nineteenth Amendment. It does not confer voting rights on anyone. This is its pith:

Section 1. The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any state on account of sex.

Advocates of woman suffrage adopted the model created by Congress to extend voting rights to freedmen after the Civil War in the Fifteenth Amendment of 1870. In that case the section ended “on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.” The wording was a compromise in both cases: it reinforced the nation’s tradition that states set voter qualifications, but it imposed new federal rules about how that would be done. In 1920, states could no longer bar women from voting by writing “male” into a state’s qualifications. That change, monumental as it was, left many women with US citizenship still unable to vote and, to this day, vulnerable to state actions that exclude them for reasons other than race, color, or sex.

Early declarations of women’s right to vote carried no instructions as to where women might secure it. Writing to a friend a few months after the meeting at Seneca Falls, Elizabeth Cady Stanton wondered: “We have declared our right to vote— The question now is how should we get possession of what rightfully belongs to us?” [1] In the spring of 1850, women in Ohio offered one answer: they called a meeting in anticipation of a state constitutional convention and circulated petitions calling for the enfranchisement of women and Black men. Soon, pioneers in the women’s rights movement were presenting their demand to state legislatures and conventions from New England to Kansas . [2]

States controlled access to the ballot box. Their constitutions defined who belonged to the club of voters and, by omission, who was excluded. They were not subtle. Wisconsin’s first constitution in 1848 expressed ideas standard to the era:

Every male person of the age of twenty-one years or upwards, of the following classes, who shall have resided in this State for one year next preceding any election, shall be deemed a qualified elector at such election.

The eligible classes of adult males were “white citizens of the United States,” white immigrants who had declared an intention to become citizens, and a small number of Native Americans not deemed to be tribal members. Neither females of those classes nor African Americans of either sex could qualify to vote. Across most of the country at midcentury the electorate was male, white, and over twenty-one. [3]

At the start of the Civil War in 1861, no women had gained voting rights, but this new movement had raised the topic of equal political rights in state and federal legal conversations. At war’s end in 1865, that mattered. For women seeking equal rights, the postwar period of Reconstruction changed the political and legal landscape. The end of slavery required that citizenship be rethought. What is it and whose is it? Prior to ratification of the Fourteenth Amendment in 1868, the United States lacked a definition of who among its residents were citizens. The amendment’s opening sentence addressed that gap:

All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside.

Though primarily aimed at recognizing African Americans as citizens, the language also removed any uncertainty about women’s citizenship. [4] Questions remained, however, about what came with citizenship. Are voting rights inherent in citizenship? Is there a federal interest in voting rights? From 1865 to 1870, these questions were major topics of national debate, and for most of that time, woman suffragists acted within an interracial equal rights movement. In many states of the North and the South, activists pressed to change state laws so that all adult men and women, Black and white, had equal rights to vote. Of hopes for New York in 1866, Susan B. Anthony told an audience: “now is the hour not only to demand suffrage for the negro, but for every other human being in the Republic.” [5] Suffragists petitioned Congress to consider the advantages of universal suffrage tied to citizenship. In December 1868, Congressman George W. Julian of Indiana introduced language for an amendment that would achieve that ideal:

The right of suffrage in the United States shall be based on citizenship, and shall be regulated by Congress, and all citizens of the United States, whether native or naturalized, shall enjoy this right equally, without any distinction or discrimination whatever founded on race, color, or sex. [6]

Julian envisaged not only a polity of equal rights among adult citizens, but also a federal government with the authority to qualify its voters.

This dream of voting rights for every citizen came to a splintered end. Congress rejected universal suffrage in favor of manhood suffrage, proposing the Fifteenth Amendment as we know it to the states in February 1869, while women in the equal rights alliance were told to stand down. Allies who were willing to campaign for manhood suffrage took that path, African American women made choices between pressing for their individual rights or accepting that votes for freedmen alone was a huge leap forward, and woman suffrage lost its connection to a movement with universal aims. In short order, in March 1869, Congressman Julian introduced a sixteenth amendment for woman suffrage, repeating his earlier language about suffrage and citizenship and slimming down the prohibitions to “founded on sex.” [7] Congress let the matter drop.

Organizations devoted to winning woman suffrage date to this postwar period. Some of them were local groups, like the first one, in St. Louis. Within a few years, dozens of states boasted an association, sometimes two, if rivals for leadership could not get along. Two organizations with national ambitions were founded in 1869. One, calling itself the National Woman Suffrage Association, planned to keep pressure on the federal government to enfranchise women. This was the group led by Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony, among many others. The American Woman Suffrage Association, led by Lucy Stone , accepted the decision to leave women’s rights to the states and resolved to work in that arena. If a major state campaign were underway, as in Michigan in 1874, both groups stepped up to help with speakers and funds. These two associations survived for twenty-one years as separate and often arguing entities.

Formal organizations were not the sole drivers of agitation about voting rights. Women took direct action to claim their right to vote in a variety of ways, especially in the hopeful years right after the war. In Vineland, New Jersey , year after year, women installed their own ballot box at the polling place and showed up on election day to vote. (Figure 1) In Lewiston, Maine , in fall 1868, a taxpaying widow of a Union soldier applied to register as a voter, one of many widows whose protests spotlighted their lack of political representation. In Washington, DC , Frederick Douglass marched with a large group of Black and white women to the registrar of elections. [8]

The idea of a citizen’s right to vote did not die with Julian’s amendment. Several lawyers argued that women had a right to vote because they were citizens and that activists should challenge their exclusion from the ballot box through test cases in the courts. In the early 1870s, what had been spontaneous actions by women to show up at the polls became more systematic as women planned lawsuits. At least six test cases reached the courts—in California , Connecticut , Illinois , Missouri , Pennsylvania , and the District of Columbia—and, after state courts ruled against women, they appealed two cases to the Supreme Court. [9] Before the court heard arguments in the case of Virginia Minor of St. Louis , a different sort of case got underway in New York, after fourteen women in Rochester successfully registered and voted. The federal government arrested and indicted them and prosecuted them for a criminal violation of federal law—voting without having the right to vote. Because one among them was very well known, the US attorney eventually proceeded only against her, and an associate justice of the Supreme Court presided at her trial.

Associate Justice Ward Hunt’s opinion in that trial, United States v. Susan B. Anthony (1873), scoffed at the idea of a citizen’s right to vote.

If the right belongs to any particular person, it is because such person is entitled to it by the laws of the State where he offers to exercise it, and not because of citizenship of the United States.

The states, he went on, could do what they wanted, provided their exclusions did not conflict with the Fifteenth Amendment.

If the State of New York should provide that no person should vote until he had reached the age of thirty years, . . . or that no person having gray hair, . . . should be entitled to vote, I do not see how it could be held to be a violation of any right derived or held under the Constitution of the United States. [10]

Susan B. Anthony was convicted of crime.

Eighteen months later, the Supreme Court heard the case of Virginia Minor. (Figure 2) Denied registration as a voter, Minor wanted the court to rule that Missouri’s limitation of voting rights to males was unconstitutional. In a unanimous opinion, the justices ruled that women were citizens of the country and thus “entitled to all the privileges and immunities of citizenship.” That was a welcome clarification, but it begged the question, what are those privileges and immunities? In the court’s view, they did not include voting rights. Writing in 1875, after ratification of the Fifteenth Amendment, the justices could agree

that the Constitution of the United States does not confer the right of suffrage upon any one, and that the constitutions and laws of the several States which commit that important trust to men alone are not necessarily void. [11]

The decisions in the cases of Susan B. Anthony and Virginia Minor not only closed a door for women but also opened doors for states. In advance of her trial, Susan Anthony had warned about the flawed reasoning:

It will not always be men combining to disfranchise all women. . . . Indeed, establish this precedent, admit this right to deny suffrage to the states, and there is no power to foresee the confusion, discord, and disruption that awaits us. There is, and can be, but one safe principle of government—equal rights to all. [12]

Once the Supreme Court ruled against Virginia Minor, suffrage activism settled into two streams, federal and state. The National association returned to advocacy of a federal amendment and used Julian’s model with its claim of universal voting rights based on citizenship. However, in 1878, an amendment modeled on the Fifteenth Amendment was introduced in the Senate. Despite the less radical language, opponents blocked its consideration for nine years. On January 25, 1887, a day that coincided with a convention of woman suffragists in the nation’s capital, Senator Henry W. Blair of New Hampshire brought the matter to the floor and the Senate finally voted on the issue. Women packed the Senate Gallery to watch senators defeat the resolution. [13] The Senate would not vote again on the amendment until 1914. In the House of Representatives, the amendment did not come up for any vote until 1915.

Meanwhile, the American association encouraged activists in states to pursue any political rights that fell within a state’s power to grant. Suffragists poured enormous resources into state and territorial campaigns, with far more lost than won. But the wins mattered to the women in the West who gained a voice in government through full suffrage. (Figure 3)

Woman suffragists did not act in a political vacuum but were influenced and constrained by national politics. In the South, the withdrawal of federal troops as part of the Compromise of 1877 closed Reconstruction and reversed the progress toward political participation made by African Americans in that region. Elections in southern states were occasions of racial violence. Federal enforcement of the Fifteenth Amendment ceased, and white southerners regained power in Congress. States in the former Confederacy set about rewriting their constitutions to put obstacles in the way of African American men registering to vote. Beginning with Mississippi’s new constitution of 1890, the states defined an assortment of ways to block or significantly reduce Black enfranchisement.

At about the same time, after the Senate vote on a woman suffrage amendment in 1887, discussion began about merging the two suffrage associations before their leaders died. There were lots of reasons, but the defeat of the amendment seemed to signal the end of an old divide and a chance for suffragists to unite around state action. Through merger, the National American Woman Suffrage Association came into existence in 1890. Attention to federal protection for a citizen’s right to vote or any federal amendment waned.

It happened, then, that in 1890, woman suffragists stopped seeking federal protection for voting rights at the same moment that southern states formalized the exclusion of Black men from the franchise. Their complicity went further. To gain ground in the white South, the National American Woman Suffrage Association affirmed in 1903 its belief in the South’s prerogative to legislate white supremacy: the association resolved, it seeks “to do away with the requirement of a sex qualification for suffrage. . . . What other qualifications shall be asked for it leaves to each State.” [14] The political equality of all citizens was no longer the organized movement’s objective.

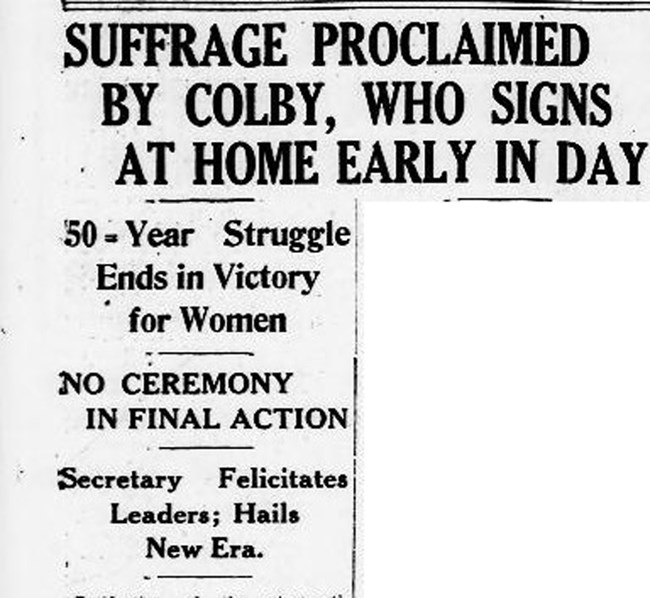

Woman suffragists turned back to the goal of a constitutional amendment in 1913 and the Senate voted on the measure in 1914—defeating it again. But this time, despite a persistent interest in keeping the focus on state actions and despite a new divide between two suffrage groups, women stayed the course and kept up pressure until both houses of Congress approved the measure in June 1919. It is this last phase, from 1913 to 1919, that produces the most striking stories and martyrology of woman suffrage history, with jail sentences, hunger strikes, and forced feeding. The images shocked contemporaries and clothed the federal government as oppressor. Less colorful was the fact that by 1919 women in fifteen states had gained full voting rights and were electing senators and members of Congress. The men who were accountable to female constituents voted overwhelmingly in support of the amendment. Like any amendment proposed to the Constitution, this one needed three-quarters of the states (thirty-six at the time) to ratify it. Those many steps took more than a year and came down to one vote in one state—in Tennessee in August 1920. It had taken decades and generations to eliminate the presumption that men had a right to govern for women. Activists had changed both law and political culture because they believed that manhood suffrage—full voting rights for men and only men—made a mockery of self-government. (Figure 4)

This huge step toward “a more perfect union” left standing the judicial decisions that a right to vote was not a fundamental right of American citizenship. Although the National Woman’s Party had referred to the Nineteenth Amendment as the “Susan B. Anthony Amendment,” it did not reflect her convictions about a citizen’s right to vote. The difference was underscored immediately in the fall of 1920 by the federal government’s decision that the women of Puerto Rico , despite their US citizenship, were not enfranchised by the amendment because citizenship did not guarantee a right to vote. [15] Their woman suffrage movement lasted until 1935.

The amendment also left in place states’ rights to exclude citizens from the rolls of eligible voters provided that the reasons for doing so were not those itemized in the Fifteenth and Nineteenth Amendments. This bow to states’ rights was a part of the amendment’s political appeal and is a part of its legacy to this day. This amendment simply meant that the state must discriminate equally. As the Equal Suffrage League of Virginia reassured the white public in 1916, speaking of the devices by which African Americans were kept at bay, “as these qualifications restrict the negro man’s vote, it stands to reason that they will also restrict the negro woman’s vote.” [16]

In northern states, African American women embraced their new right to vote and used its power to press for racial justice and equality. The experience of African American women in states of the former Confederacy was not uniform, and it took several years for officials to complete the job of disfranchisement. Some women managed to register and vote in the presidential election in 1920. But across much of the South, equal discrimination subjected African American women to well-practiced tactics designed to discourage and/or disqualify them as voters. William Pickens, of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, reported on voter registration in Columbia, South Carolina , a state where African Americans made up the majority of the population. Registrars were surprised at the high numbers of Black women who lined up to register, he wrote. They relied on a familiar tactic, “white people first,” leaving women of color standing for hours. On the second day, these women “were made to read and even to explain long passages from the constitutions and from various civil and criminal codes.” [17] White supremacists of South Carolina followed the path etched in Ward Hunt’s conviction of Susan B. Anthony, the same one later ratified by the National American Woman Suffrage Association’s promise to the South in 1903, that states could invent whatever qualifications for voters they desired, so long as there was no sex qualification. It took forty-five years to win the Voting Rights Act of 1965 that protected the rights for people of color, women and men, across the South.

To close the history of woman suffrage at 1920 is to ignore those women left behind in 1920, women who still dreamed of equal political rights. It is also to ignore how precarious the victory, how easily women can lose their ability to vote if the state where they reside exercises its right to exclude people, and to forget that freedom without voting rights is a mockery, whoever you are.

Ann D. Gordon is Research Professor Emerita of History at Rutgers University. She has studied the movement for woman suffrage for nearly four decades as an author, editor, and lecturer. She was chief editor of the prize-winning collection of essays African American Women and the Vote, 1837–1965 (University of Massachusetts Press, 1997). She also edited the six-volume Selected Papers of Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony (Rutgers University Press, 1997–2013).

Notes:

[1] Elizabeth Cady Stanton to Amy K. Post, September 24, 1848, in Selected Papers of Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony, ed. Ann D. Gordon et al. (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1997), 1:123. Hereafter SAP.

[2] For an overview of this early spread of women’s rights activism, the best source is still the first volume of the History of Woman Suffrage, ed. Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony, and Matilda J. Gage (New York: Fowler & Wells, 1881).

[3] Wisconsin’s provision for noncitizens to vote spread, until by 1890 in seventeen states a declared intention to become a citizen was sufficient to qualify men to vote. The variety of ways that states found to exclude residents from voting in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries are conveniently tabulated in Alexander Keyssar, The Right to Vote: The Contested History of Democracy in the United States (New York: Basic Books, 2000), appendix.

[4] Native Americans living under tribal government were defined as not “subject to the jurisdiction” of the federal government and therefore not citizens despite their birthplace.

[5] Remarks to Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society, November 22, 1866, SAP, 1:605.

[6] Joint Resolution, H.R. 371, 40th Cong., 3rd sess. (1868).

[7] Joint Resolution, H.R. 15, 41st Cong., 1st sess. (1869). A word about numbers: Sixteenth Amendment was the designation of a proposed woman suffrage amendment from 1870 until 1913, when two amendments were added to the Constitution. An amendment allowing a federal income tax became the sixteenth and a change in how senators were elected, from legislative action to direct popular vote, became the seventeenth. In 1919, an amendment to prohibit the making and selling of liquor became the eighteenth.

[8] Examples of direct action by women in this period are compiled in Appendix C, “Women Who Went to the Polls, 1868 to 1873,” SAP, 2:645–654. Also available at http://ecssba.rutgers.edu/resources/wompolls.html.

[9] Two cases from the protest in the District of Columbia were on the docket for the Supreme Court for fall 1873, but after two postponements, the court passed over the case. Minutes of the Supreme Court of the United States, vol. 31, December 11, 1873, and vol. 32, October 16, 1874, RG 267, National Archives.

[10] United States v. Susan B. Anthony, 11 Blatchford 200, 204 (1873). For more on this trial and its context, see the Federal Judicial Center’s site .

[11] Virginia Minor v. Reese Happersett, 21 Wallace 162, 178 (1875). See also the National Park Service site.

[12] “Is It a Crime for a U.S. Citizen to Vote?” January 16, 1873, SAP, 2:569.

[13] Congressional Record, 49th Cong., 2nd sess., January 25, 1887, pp. 986–1003. See also coverage in Washington Post, January 26, 1887.

[14] National American Woman Suffrage Association Business Committee to Editor, Times-Democrat (New Orleans), March 18, 1903, SAP, 6:470.

[15] See Allison L. Sneider, Suffragists in an Imperial Age: U.S. Expansion and the Woman Question, 1870–1920 (New York: Oxford University Press, 2008), 129–134.

[16] Broadside, “Equal Suffrage and the Negro Vote,” Equal Suffrage League of Virginia, Virginia Historical Library, Encyclopedia Virginia.

[17] William Pickens, Nation, October 6, 1920.

Bibliography

Berman, Ari. Give Us the Ballot: The Modern Struggle for Voting Rights in America. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2015.

Gordon, Ann D. et al., eds. African American Women and the Vote, 1837–1965. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1997.

Gordon, Ann D. et al., eds. Selected Papers of Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony, 6 vols. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1997–2013.

Keyssar, Alexander. The Right to Vote: The Contested History of Democracy in the United States. New York: Basic Books, 2000.

Matthews, Jean V. The Rise of the New Woman: The Women’s Movement in America, 1875–1930. Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 2003.

———. Women’s Struggle for Equality: The First Phase, 1828–1876. Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 1997.

Monnet, Julien C., “The Latest Phase of Negro Disfranchisement.,” Harvard Law Review 26, no. 1 (November 1912): 42–63 .

Sneider, Allison L. Suffragists in an Imperial Age: U.S. Expansion and the Woman Question, 1870–1920. New York: Oxford University Press, 2008.

Winkler, Adam. “A Revolution Too Soon: Woman Suffragists and the ‘Living Constitution.’” New York University Law Review 76 (November 2001): 1456–1526.

“ Virginia Minor and Women’s Right to Vote ,” Gateway Arch National Park and Old Courthouse, St. Louis, Missouri, last updated January 16, 2018.